- Home

- Louise Steinman

The Souvenir Page 2

The Souvenir Read online

Page 2

And at the same time, the troop ship carried him closer to an enemy he did not know and did not understand—an enemy he was in no hurry to encounter.

Stateside

CHAPTER ONE

The Pharmacist

“YOU’RE NOT LISTENING,” my father used to say when I tried to slip an opinion in edgewise. In any discussion, his was always the last word.

Norman Steinman was a patriarch. Responsible, overburdened, overbearing, tender in his distant way. My father loved to give advice. Even more, he expected to be asked for advice. A Rexall pharmacist, he believed there was a palliative for any kind of illness or physical distress. Emotional distress was not in his purview. His own, he kept private.

Except for some well-worn anecdotes about bossy sergeants and his camaraderie with the characters Captain Yossarian of Catch-22 and Hawkeye from M*A*S*H, he never talked to his children—or anyone else I knew—about his experiences in the Pacific in World War II. He discussed neither his losses nor his sorrows.

In our permissive household, there were few edicts beyond the obvious, like “Stay away from the stove, it’s hot.” Perhaps that’s why the few my parents insisted upon stood out. There were three. The first: Never cry in front of your father. Why? “It reminds him of the war.” The second: Never wear black in your father’s presence. Why? “It reminds him of his sister, Ruth, who died when she was fourteen.” The third: Don’t question these rules. Though debate and questions were encouraged in our rambunctious household, these givens were so absolute, my three siblings and I simply accepted them. Whatever happened to him “over there” in the war was off-limits, like a nuclear test zone.

We were admonished never to provoke my father’s anger—infrequent but explosive. We were told it was a function of his fatigue. When he was angry or depressed, a familiar and untouchable bad feeling permeated the house. Usually, he just smoldered, but on those occasions when he blew his top, the household froze in its tracks until he retired to his room and slammed the door with reverberating force.

Our doting Russian grandmother used to sigh and say, “The war changed your father. He never had a temper before the war.” I never tried to imagine what Norman Steinman was like before the war changed him, or just how this change might have occurred.

After his big heart attack, when he was fifty, my father’s doctor advised him to avoid emotional outbursts of any kind. Yet some were as unavoidable as they were inexplicable. One night my mother served him sauerkraut, and he threw the whole plate against the wall. “Something to do with the war,” she mumbled as she cleaned up the mess. The mere smell of “Oriental” food made him nauseous. “Reminds him of the Philippines,” my mother whispered. The whistling tea kettle was banned from our kitchen. The hissing sound unnerved him. Again, “something to do with the war.”

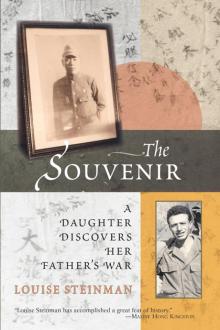

Were it not for a chance discovery, my father’s silence about the war might have accompanied him to his grave. While cleaning out my parents’ condo in 1991, after my father and then my mother died, I unearthed a metal ammo box from a storage locker in the underground garage. Inside were hundreds of letters my father wrote home to my mother from the Pacific War. In one of those envelopes was a Japanese flag with handwritten characters inked across its fragile face.

These letters, this flag, propelled me on a circuitous, decade-long journey that challenged me to learn more about my father and the men of his generation who fought in the Pacific. To the question, What was Norman Steinman like before he went to war? I would find some answers. But new mysteries would also reveal themselves.

IN THE DECADES after he returned home from the Pacific, my father’s attention, like that of so many others of his generation, was focused on building a business, providing for his family. He opened his first pharmacy in 1951. Pinned to the bulletin board over my desk is a black-and-white snapshot that shows my parents standing behind the counter on opening day.

They were in their thirties, younger than I am now. My father looks dapper in his white druggist’s smock. My mother wears a shirtwaist dress and pearls. They had followed his parents west from New York City after he was demobbed from the army in 1946. They were both eager to raise their children in the bright California light. Wanting a fresh start, my father attended the University of Southern California School of Pharmacy courtesy of the GI bill. My mother ran the house until the youngest of her four was junior high age, and then she embarked on a twenty-year career as a Head Start teacher.

Small and stalwart, my parents both smile into the camera. A banner behind them—OPEN SUNDAY 9 a.m. TO 9 p.m.—testifies to my father’s impossibly long hours. In the early years of establishing his business, he worked twelve hours a day, seven days a week. Most nights, he came home and went straight to bed, waking an hour later to eat supper alone. Displays of Ace combs and Gillette razors, Crest toothpaste, laxatives, and a zany pair of giant cardboard spectacles with the phrase “Look to Us!” surround the beaming couple.

In the fifties, Edwards Rexall Pharmacy, my father’s store on Sepulveda Boulevard in Culver City, was the hub of our family’s well-being and a regular hangout for the neighborhood. (The business came with the name Edwards but we never found out who he was.) The regulars parked themselves in the chrome armchairs by the back counter, airing and comparing their malaise. Those without prescriptions consulted with “Doc” Steinman. He recommended tranquilizers for the nervous rabbi, Kaopectate for the wife of the high school principal, Vi-Daylin to pep up Mr. Alfano from the Villa Italian restaurant next door. A “cousins club”—one large extended family including new arrivals from Kiev and Buenos Aires—received discounts on aspirin, cosmetics, antibiotics.

My siblings and I all worked in the store at one time or another. My after-school job was counting pills from large brown bottles into smaller dark bottles in the back room. Kenny, my younger brother, delivered prescriptions in the red Corvair, dreading the nursing homes where skinny arms reached out to touch him. My older brother, Larry, often worked the counter. “When men wanted to buy condoms, they used signals,” he recalls. “Two fingers on the counter, like legs apart.” My sister, Ruth, wrapped boxes of Kotex sanitary napkins in plain brown paper before arranging them on the shelves. Reticence and modesty were the era’s reigning virtues.

At least once a week we drove over to my grandparents’ apartment building, twenty minutes by car. On the way, I always marveled at the giant painted “sky” movie backdrop on the MGM lot. As wide as a football field, this “sky within the sky” could be daylight blue, twilight gray, sometimes inky black. Culver City was the “Heart of Screenland,” and illusion was the hometown product. Sniffling movie stars dispatched limos to my father’s pharmacy. He loved to tell us how he’d advised Woody Allen to take Chlor-Trimeton. (“He was all stuffed up, a terrible cold. A real gentleman.”)

Aside from nitro pills for his heart, my father seldom took as much as an aspirin himself. Nevertheless, he believed in drugs for everyone else. He dispensed Preludin to Ruth for her diets, Benadryl to his wife for hay fever, and Ritalin to me when I needed to pull an all-nighter to study for European history finals. After supper, while I watched Mickey Mouse Club, he ordered from the McKesson Company, chanting those magical names into the phone: “One only Phenobarb, two only Doriden, four only Librium, one dozen Penbritin, four ounces paregoric.”

The man had an uncanny ability to reduce any situation to its pharmaceutical implications. In 1988, he surveyed my proposed wedding site in Topanga Canyon, north of L.A., noted the blooming chaparral, and soberly proclaimed, “Everyone will need Seldane.”

If you felt sick, you were expected to “take something.” If you refused to help yourself, he’d cross his arms, sigh, wait out an effective pause, and grumble those dreaded words: “Then suffer.” It always worked. If you refused to take something he recommended, you were then beyond the realm of his protection, the safe haven that only Western medicine and a strong rational father could provide.

By the mid-fifties, my parents own

ed their own home, a boxy stucco three-bedroom house at 4045 Harter Avenue, a nearly treeless Culver City street lined with similar postwar single-family houses. An eggplant-purple Oldsmobile sedan was parked in the driveway. The centerpiece of the all-concrete backyard was the small built-in swimming pool where Ruth, who’d contracted polio when she was six, could swim to strengthen her limbs.

Every four years or so, my father replaced the family car with a new model, a badge of membership in the postwar consumer adventure. He always bought American. The night he arrived home from work in the new Olds, or Ford, or Mercury, was as close as our family ever came to a spontaneous holiday. “Can we go for a drive?” we’d all squeal. And Norman, proud as punch, still in his pharmacy smock, would take his brood for a spin, past the Big Doughnut and the Rollerdrome, the Little League field, the Culver Municipal Plunge.

My father worked long hours so that my siblings and I could attend summer camp, so that my brilliant older brother could take special math and science classes, so that my sister had the best in orthopedists, physical therapy, leg braces. His earnings paid as well for the adjunct helpers to our growing household. Mr. Smith, the pool man, a tall, lanky redhead from Oklahoma, who parked his battered pickup once a week in front of our house, unlatched the gate to the pool yard, and with his long-poled nets expertly scooped dead bugs from the turquoise-hued water. Bessie Greggs, a wry, wisecracking black woman who made the world’s best BLTs, came three times a week to help with the housekeeping. A nervous Israeli named Raul tutored my brother in Hebrew. Once a week a handsome Nisei man—nicknamed Porky—mowed the modest lawn and clipped the boxwood hedges. My father respected Japanese Americans, who had served as interrogators with his division in the Pacific.

Porky brought vegetable seeds, and together we’d plant rows of carrots. He showed me how to transplant begonias, aerate lilies. I would kneel beside him and crumble the soil with my hands. He wore a battered khaki porkpie hat that shielded the deep wrinkles in his sunburned brow. My mother told me Porky’s family had been in a camp during the war. The camp, with the exotic name Manzanar, was not in Germany, but in California. I was astonished. How could that be?

I’d heard about the concentration camps in Europe. I solemnly observed my parents’ choked-up references to nameless relatives “who didn’t make it out of Poland or Russia.”

One night when I was eight, my mother, who had never forced me to do anything, stormed into the dining room and switched the TV channel from Zorro. I protested. Don Diego was on the verge of rescuing a hapless señorita. Mother insisted I sit and watch what was on the screen. Her sternness alarmed me. I didn’t budge.

It was a documentary about the liberation of the camps in Europe. Eisenhower was there, wearing a greatcoat, walking slowly past bony men with hollow eyes. White bones and ashes poured out of ovens. Piles and piles of shoes. A mound of human hair. I didn’t want to watch, but I couldn’t stop looking. Bodies dumped off wheelbarrows into open pits. An arm askew. Faces of the living without expression. A strange sound grew louder than the announcer’s somber voice—Mother’s stifled sobs.

That night, gaunt bodies pursued me in dreams. The earth yawned open, huge dogs herding my family toward the chasm. The next day at school, I took odd and spontaneous revenge—ripping the pages on Hitler out of the encyclopedia.

It went without saying that nothing made in Germany was ever to be brought into our home. Not even those lifelike Gund stuffed animals I admired at FAO Schwarz. Those hip Volkswagen beetles my friends drove in the sixties elicited my parents’ disgust. They also refused to buy Japanese goods—though that made little impression on me. Back then, MADE IN JAPAN was a joke, anyway. You opened the box, the toy fell apart.

As a young child, I was aware of the visceral horror of the Holocaust. By contrast, the Pacific War was distant and vague. There were no books, no photos that impressed upon me the barbarity of the campaign my father fought in northern Luzon against the Japanese. I saw no documentaries about emaciated American POWs in Burma or Bataan, no images of mass suicides of civilians on Okinawa. True, there was the other “H”—Hiroshima—that blasphemy tied to the anxiety hanging over us. But I never made the connection between that tragedy and my father’s unmentionable experiences in the war.

I absorbed the general notion that my father had fought a war to make our world on 4045 Harter Avenue in Culver City safe from fascism and military dictatorship. And—at least until the Cuban missile crisis in 1962—it did feel safe.

I never doubted that my parents loved us, but I was slow to realize how they sacrificed their personal pleasure to ensure the well-being of their children. Our well-being was their pleasure. From time to time, my mother gently reminded us how hard Dad was working. Now, when I compare memories with Ruth, it’s obvious that he was depressed. “So melancholy,” she recalls. “Something was eating him up from the inside.”

That I knew so little about Norman Steinman’s inner life, or even that he had one, was as much a function of a child’s self-involvement as it was a function of the blackout on his emotional history.

I had no idea back then why he longed for normalcy, for quietude, for a small town like Culver City. I had no idea what a feat it was to make a home, a life, and a world of possibilities for your children. I did not yet understand why my father believed if there was a cure for what ailed you, why suffer?

CHAPTER TWO

The Flag

MY FATHER LIVED the last two decades of his life as a cardiac cripple, but he was secretive about the extent to which he suffered from angina. He avoided cold climates, restricted his exercise, never tossed a baseball with his youngest son. He’d furtively slip a vial of nitroglycerin out of his pocket and put a tiny pill under his tongue whenever it got cold, whenever he walked more than a block, after eating a big meal. He reached for that vial by the ocean: he took it out after climbing the steps to my apartment. Since I thought of the nitroglycerin as a last resort, his dependence on it alarmed me, but he’d just wave me off, irritated. He was a prime candidate for bypass surgery or angioplasty, but the truth was the pharmacist was wary of doctors and feared invasive procedures.

I was in New York when my father died in Los Angeles in 1990. Later, I learned that he had not felt well the whole week prior, but he had stubbornly refused to see his cardiologist. Finally, when he couldn’t hide the pain from the angina, my mother convinced him to go to the hospital. “Don’t drive so fast,” he scolded her. “It’s not a matter of life or death.”

In the emergency room, he took off his watch and pulled his wallet out of his back pocket. He handed them to my mother. “He knew,” she told me. “I could tell by the fear in his eyes.” The nurses drew the curtains. The doctors applied the shock paddles, but he was gone.

It was three a.m. in Manhattan when my friend Wendy, a wraith in her long white nightgown, glided into the guestroom and gently shook me from a sound sleep. “Lloyd called. Call him right away.” I dialed my husband in Los Angeles.

Had this really happened? My father had suffered his first heart attack twenty-six years ago, when he was just fifty. He had always lived in fear of the next one, but I felt completely unprepared for his loss.

By the time I arrived at my parents’ condo in Los Angeles, my siblings were already gathered there. My usually ebullient mother was in shock. The portly upstairs neighbor wheeled in a shopping cart containing two boiled chickens and a pot of broth. My father had always hated this good neighbor’s soup.

Ruth and I ordered platters of turkey, pastrami, ham from the deli around the corner. My mother set out pastries and cake, made huge pots of coffee. Relatives—Russians, Argentineans, former Brooklynites residing in the San Fernando Valley—all crowded in.

My father, reliably unsentimental, once explained to me his version of the origin of the wake. “In the old country,” he said, “people traveled long distances on horseback and in carriages. It was too far to go back the same night. They expected to be fed.”

; For the rest of the afternoon, whenever any of the cousins or neighbors looked chilly, my mother instructed Larry or Kenny to bring one of my father’s jackets from his closet. In the pockets of every one of his jackets was a vial of nitroglycerin. “Enough to blow up the whole building,” Larry, the doctor, said grimly. He flushed all the nitro down the toilet.

Larry and Kenny stepped boldly into the patriarchal breach. They decided on a traditional Jewish burial even though our father was not observant. He would be bathed, wrapped in a linen shroud, and buried in a plain pine coffin. Anonymous men, religious Jews, would be paid to sit by his body during the night and sing psalms.

I wanted to see my father one last time. Kenny cautioned me: “He won’t be embalmed. He won’t look good. His ears are blue.” The grief counselor at the Garden of Eden mortuary also considered the request unusual. However, for a fee, the mortuary agreed to prepare him for a last visit.

Lloyd and I drove across town to the Garden of Eden. It was late night in L.A., and even later by New York time. We’d been told the front door to the mortuary would be open. We walked inside; no one was there. The place was eerily quiet. We pushed on the door marked CHAPEL. At the far end of the room, my father lay on a gurney skirted in red velvet pleats and framed by an arch of red velvet curtains.

In life, his personal demeanor had never, even remotely, verged on the theatrical. For this last viewing, however, his naked body was attired in classically draped white sheets. There were two empty chairs beside the body; Lloyd and I both sat down. Kleenex boxes were placed strategically within reach.

The Souvenir

The Souvenir