- Home

- Louise Steinman

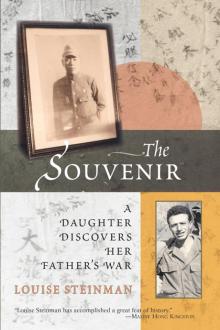

The Souvenir

The Souvenir Read online

Praise for The Souvenir

“Exceptional … a graceful, understated memoir … that draws its strength from the complexities it explores.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Ms. Steinman skillfully weaves her father’s emotional letters into the present-day story line, sensitively taking readers through Norman Steinman’s transformation from naïve American soldier to hardened combat veteran.… The Souvenir underscores the indescribable way war affects not only veterans but also their families and future generations.”

—The Dallas Morning News

“The book is the story of entwined ‘gifts’ resulting from [a] personal journey—Steinman’s discovery of a side of her father she never expected to share. For many, her account could provide an understanding of how the war changed one generation and shaped the next.”

—Library Journal (starred review)

“A moving memoir about reconciliation and honor.”

—Publisher’s Weekly

Winner of the Gold Medal in Autobiography/Memoir from ForeWord magazine

ALSO BY LOUISE STEINMAN

The Knowing Body: The Artist as Storyteller

in Contemporary Performance

Copyright © 2001, 2002, 2008 by Louise Steinman. All rights reserved. No portion of this book, except for brief review, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the written permission of the publisher. For information contact North Atlantic Books.

Published by

North Atlantic Books

P.O. Box 12327

Berkeley, California 94712

Cover design by Susan Quasha

First published by Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2001.

The Souvenir: A Daughter Discovers Her Father’s War is sponsored by the Society for the Study of Native Arts and Sciences, a nonprofit educational corporation whose goals are to develop an educational and cross-cultural perspective linking various scientific, social, and artistic fields; to nurture a holistic view of arts, sciences, humanities, and healing; and to publish and distribute literature on the relationship of mind, body, and nature.

North Atlantic Books’ publications are available through most bookstores. For further information, visit our website at www.northatlanticbooks.com or call 800-733-3000.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Steinman, Louise.

The souvenir : a daughter discovers her father’s war / Louise Steinman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

Summary: “The Souvenir presents a legacy of war stories left inadvertently to a daughter by a father who only wished to forget. At turns poetic and journalistic, Steinman’s cross-generational memoir asks vital questions about the impact of war and views the fallout of a soldier’s secrets by one daughter’s probing light”—Provided by publisher.

eISBN: 978-1-58394-790-6

1. Steinman, Norman, 1915–1990. 2. United States. Army—Biography. 3. Pharmacists—United States—Biography. 4. World War, 1939–1945—Biography. 5. United States. Army. Infantry Division, 25th—Biography. 6. World War, 1939-1945—Campaigns—Philippines. 7. World War, 1939–1945—Japan. 8. Steinman, Louise. 9. Steinman family. I. Title.

U53.S74S74 2008

940.54′25991092—dc22

[B]

2007051527

v3.1

TO THE MEMORY OF MY PARENTS,

ANNE WEISKOPF STEINMAN (1919–1990)

AND NORMAN STEINMAN (1915–1990)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MANY PEOPLE HAVE ASSISTED ME on this long journey.

Many thanks to Rika Ohara, for first translating the flag; John Mellana, who pointed me in the direction of John Dower’s work; Howard Junker, who published my long poem about Yoshio’s flag in his magazine zyzzyva; editors Susan Brenneman and Bret Israel at the Los Angeles Times Magazine, who gave me the assignment to Japan; Paul Freireich at the New York Times travel section for his invaluable sleuthing; and Donna Frazier, who edited my article for the Los Angeles Times Magazine and in the process became a friend and trusted guide. At Algonquin, thanks to Elisabeth Scharlatt and Ina Stern who offered spiritual support.

I’m indebted to Lindy Hough and Richard Grossinger at North Atlantic Books for giving The Souvenir a new life. It’s been a pleasure to work with editor Elizabeth Kennedy and publicist Allegra Harris on their fine team.

Thanks to my wonderful family—to the late Florence Hamrol, a memorist herself; to Matthew Solomon, who provided many details from his memory; to Jennifer Solomon, who made the scrapbook of newspaper clippings about her grandfather’s stint in the Pacific; to Larry Steinman, who asked critical questions and read the poem at Passover; to Ruth Solomon, for her encouragement and insights; and to Ken Steinman for stories and support.

For straight talk, nudging, notes on the manuscript, and practical advice about Japan, many thanks to Alan Brown. Thanks to Amy Morita for being the liaison with the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare. Judith Nies offered detailed read-throughs of the manuscript. Thanks to Adam Hochschild for inspiration and encouragement, and to Professor John Dower for the afternoon he spent with me, for taking my project seriously.

Thanks to Susan Banyas, Charlotte Hildebrand, Irene Borger, Erica Clark, for listening and sharing their stories. Thanks to the following for various support over the years of writing: Steve Clorfeine, Anne Dubuisson, Suzanne Edison, Sally Kaplan, Joan Kreiss, Sarah Jacobus, Meredith Monk, Anna Valentina Murch, Regina O’Melveney, Dennis Palumbo, Roger Perlmutter, Wendy Perron, Chris Rauschenberg, Jim Siegel, Don Singer, Janet Stein, Laura Stickney, Beth Thielen, and Ellen Zweig.

Other helpers provided translation and information. Yukiko Amaya, Nancy Beckman, Gen Watanabe, Chiyoko Osborne, and Salud Ilao—many thanks.

Special thanks to Centrum Foundation in Port Townsend, Washington, for providing the environment in which my father’s letters first came alive; to the California Community Foundation for the Brody Literary Fellowship, which facilitated my first trip to Japan; and to Blue Mountain Center for the blessing of a month of peaceful writing and thinking. The good folks at the Japanese National Tourist Organization helped me find my way around Japan, and provided assistance with lodging and rail travel. Thanks also to International House in Tokyo, for their formidable library. The Library Foundation of Los Angeles accommodated my travel and writing retreats and offered a supportive atmosphere in which to work. The librarians and staff at the Los Angeles Public Library daily manage to work miracles, and I thank them for their assistance.

In Japan, the Shimizu family and their neighbors and friends received me with love in their hearts. Many thanks to Mayor Ikarashi and Mihara Kenzo for their many kindnesses. I am indebted to Mrs. Seito, Mrs. Nakamura, Mr. Watanabe, and Mr. Abe for sharing their stories. In Hiroshima, thanks to the Kurokami family for their delightful hospitality, especially to Shoji Kurokami for being my guide. In Tokyo, thanks to Marcy and Lauren Homer. At the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare, Mr. Chitaru Satake—whom I never met in person—was the indefatigable detective behind the scenes.

Thanks to my “muses,” all World War II vets and all very wise men: Sylvan Katz, Peter Lomenzo, Baldwin Eckel, and the late Fred Rochlin. They shared their difficult experiences with me, and accepted my naivete with grace and generosity. Their stories have moved me deeply and I am honored to help share them with others.

There are four more people without whom this whole project would not have been possible: Betsy Amster, my wonderful agent who is also a fine editor, was patient, prodding, enthusiastic, and honest during these many years. She always believed that “Y

oshio” would be a book and encouraged me to take whatever time was necessary to finish it. Antonia Fusco, my editor at Algonquin Books, recognized this story in the rough and made it a far better telling. Working with her is a privilege and a pleasure. Masako Hayakawa was more than a translator. She was my cultural guide, a true friend and stalwart ally who made real sacrifices to assist me. I am deeply indebted to her as well as to her husband, Professor Norio Hayakawa, for sharing his story. Finally, my deepest gratitude to my husband, Lloyd Hamrol, who accompanied me to the mountaintop, took photographs while suffering the flu, cooked dinners, edited, brainstormed, suffered my doubts, weathered my manias, fed the cat, listened to dreams, offered structural insights and unconditional love.

CONTENTS

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Chronology

Epigraph

PROLOGUE

Somewhere at Sea

PART I: Stateside

The Pharmacist

The Flag

Into the Deep

A Melancholy Slav

Speculation

The Gift

Questions

PART II: Japan

Bombs under Tokyo

Shrine of the Peaceful Country

Shadows

Amazing Grace

PART III: The Philippines

The American Cemetery

Journey to Balete Pass

Promised Land

PART IV: Suibara

Swans in the Morning

Flyover

Afterword to the New Edition

Book Group Questions

Selected Bibliography

About the Author

CHRONOLOGY

7 December 1941 Japanese attack U.S. Pacific Fleet anchored in Pearl Harbor, Honolulu, Hawaii.

8 December 1941 Japanese planes bomb Philippine city of Baguio in northern Luzon.

11 March 1942 General Douglas MacArthur retreats from Corregidor, Philippines, after declaring, “I shall return.”

August 1943 Newly drafted Private Norman Steinman arrives at Camp Fannin, Tyler, Texas, for infantry training.

January 1944 Private Norman Steinman ships out from San Francisco, crosses the Pacific to join Twenty-fifth “Tropic Lightning” Infantry Division in Auckland, New Zealand. Assigned to Headquarters Company, First Battalion, Twenty-seventh Infantry Regiment “Wolfhounds.”

Late February 1944 Twenty-fifth Division lands at Noumea, principal city New Caledonia, for further combat training. “Tropic Lightning” expected to return to fighting lines in June.

June 1944 Tactical plans change. Twenty-fifth remains on New Caledonia for more training. Rehearsals for landing on beaches in Luzon Campaign.

7 December 1944 Twenty-fifth Division convoy, known as Task Unit 77.9, moves out of Noumea, New Caledonia.

21 December 1944 Tetere Beach, Guadalcanal. Twenty-fifth Division stages “dress rehearsal” for landing at Lingayen Gulf.

11 January 1945 Private First Class Norman Steinman lands with Twenty-fifth Division at Lingayen Gulf, northern Luzon, Philippine Islands. Landing unopposed by Japanese troops.

12 January to 10 February 1945 Central Plains phase of Luzon Campaign, including battle for Umingan.

10 February to 21 February 1945 Redeployment and readying for coming assault in Caraballo Mountains of northern Luzon.

3 March 1945 U.S. forces retake Manila from Japanese.

February through June 1945 Battle to secure Balete Pass in Caraballo Mountains, drive from Balete Pass to Santa Fe, and subsequent “mop up” of Japanese hiding out in mountains.

13 May 1945 American forces declare Balete Pass “secure.”

16 May 1945 Brigadier General James “Rusty” Dalton of Twenty-fifth Infantry killed in sniper attack while on reconnaissance mission at Balete Pass.

6 August 1945 Atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima from the Enola Gay under orders from President Truman.

9 August 1945 United States drops second atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

12 August 1945 Japanese announce surrender.

15 August 1945 Emperor Hirohito’s radio broadcast to his nation asks them to “endure the unendurable.”

2 September 1945 Japanese officials formally surrender to Allies aboard U.S. battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

2 September 1945 General Yamashita, commander of Japanese troops in Luzon, surrenders to U.S. forces.

24 September 1945 Corporal Norman Steinman and others of Twenty-seventh Infantry Regiment board USS Natrona bound for Nagoya, Japan, as part of the U.S. occupation forces.

27 October 1945 After an eighteen-day offshore delay in Wakayama Harbor, Corporal Steinman and other members of the Twenty-seventh Infantry Regiment disembark at Nagoya Harbor.

31 December 1945 Corporal Norman Steinman returns stateside, disembarking in Portland, Oregon, with overnight stay at Vancouver Barracks, Vancouver, Washington.

THE SORROW OF WAR inside a soldier’s heart was in a strange way similar to the sorrow of love. It was a kind of nostalgia, like the immense sadness of a world at dusk. It was a sadness, a missing, a pain which could send one soaring back into the past.

Bao Ninh, The Sorrow of War

PROLOGUE

Somewhere at Sea

IN JANUARY 1944 when my father crossed the Pacific for the first time, he did not know where he was going. He did not know he was headed for New Zealand. He did not know that after a year of training and waiting, first in New Zealand then in New Caledonia, he and his army buddies in the Twenty-fifth Infantry Division would be transported to northern Luzon, the Philippines, where they would sweat out five and a half months of combat.

The monotony, the uncertainty of the destination, the hot sun, the loneliness, the roiling sea all took their toll on him. “I’ve never felt so blue. It’s the thought of leaving you. I hope I can get over it soon, because it’s a terrible state of affairs,” he wrote to his wife—my mother—from the confines of a transport ship.

As the realization of a long separation sank in—months, possibly years—his mood veered toward panic then settled into depression. Writing letters was his only relief. “Dear Anne,” he wrote home, “I’m sorry that you won’t hear from me for such a long time until you get this letter, but because of the safety precautions and secrecy involved (for our own good), I wasn’t allowed to tell you when I left the States.” To describe his location, he wrote simply “Somewhere at Sea” in the upper right-hand corner of each letter.

My father—a graduate of De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx, with a math degree from New York University—was lacking his usual reference points. No Sunday New York Times, no conversations with his parents, no weekly lectures at the 42nd Street branch of the New York Public Library. And the most grievous lack of all—his wife.

It was not like the pragmatic father I knew to daydream, sitting motionless, spinning in his imagination every inch of his wife’s body. Her hair. Her smile. The way she wore hats. He composed letters in his mind, wrote them down when the seasickness abated.

9 January 1944, Somewhere at Sea

Dear Anne,

Since this letter will be censored it is difficult to write. We have already adjusted ourselves to this life at sea. A sailor’s life isn’t so bad after all.

The first day nearly everyone was seasick. I must admit I was nauseous but I didn’t have to feed the fish and it passed very quickly. It was hard to adjust to sleeping in a hammock. But even that isn’t so bad when you get used to it. The only thing that none of us can possibly get used to is the congested quarters we live in.

I should have started this letter several days ago but I just couldn’t get in the mood to because I was very despondent about leaving and everything that means. Also I knew this letter wouldn’t be mailed until we arrived at some port.

I spend almost the entire day on deck, where, when the

sun isn’t too hot, it is deliciously cool. I keep looking out at the blue ocean and dreaming that you’re beside me and, when the moon is out, especially then, I just keep talking to you all the time.

10 January ’44, Somewhere at Sea

Dear Anne,

The sun was exceptionally strong today. We were warned not to be exposed in any way to the sun’s rays.

I’m sitting on the upper deck gazing out at sea. The wind is whipping at my paper and almost blowing my hat off. Yesterday when I wrote to you, the wind swept one of the pages away.

I’m smoking my corncob pipe and I’ve just finished dinner. I should be content but I’m still very melancholy. I keep thinking of you so much. I had better pull myself together otherwise I’ll be acting like a moron.

The ocean is lovely. It’s a deep blue color—almost a navy blue. As the boat moves forward, sometimes small fish fly out of its way. I have seen a large fish—one fellow said it was a shark, but I don’t believe that. This just makes me think of the Aquarium in Chicago. I always think of the things we did together. I’m glad we did everything together. You see how my mind works.

As each day goes by, it gives me a very funny feeling to realize how much farther and farther I am sailing away from home. Please believe that I’ll be thinking of you constantly. Please have faith in me that I’ll come back to you just as soon as the damned war is over.

My heart is heavy but it can’t be helped. We just will not be able to see each other for the duration.

You must promise to take care of yourself, because you know how much it will mean to me to know that you are all right.

I love you very much—and I kiss you good night.

The churning motors of the troop ship carried United States Army Private Norman Steinman, serial number 32983436, age twenty-eight, to a latitude farther south than he had ever ventured. Farther from my mother, pregnant with my sister, their first child. Farther from the future he had imagined before the war. Farther from the self he inhabited and could never return to, farther from the person his children would never meet.

The Souvenir

The Souvenir