- Home

- Louise Steinman

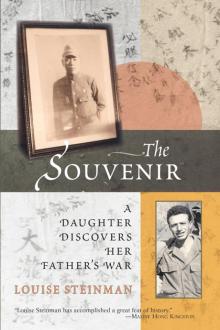

The Souvenir Page 4

The Souvenir Read online

Page 4

I wanted to try to understand the connection between my father’s silence about the war and our family’s home life. I wanted to understand the ordeals that compelled Norman Steinman to assume a new mode of being.

I figured if I could just lock myself in a cabin with all those letters, I might unravel the narrative of those war years and comprehend some truth about the man, his experience, his pain. I wanted to know how the war changed him.

We arrived at Fort Worden late at night and followed the map to our assigned domicile. I’d imagined our living quarters would be one of the fine Victorian officer’s houses on the main quad, like the ones in An Officer and a Gentleman, which had been filmed here. But cottage #255, originally intended for an enlisted man and his family, was a simple wooden bungalow. Three bare little rooms, a woodstove, some dilapidated furniture.

The next morning Lloyd and I set up my computer in the little office that faced south into the woods, and brought in extra tables to make a modest studio for him in the dining room. Lloyd, a sculptor, would use this time to paint.

I pinned on the wall a large 1945 map of the Philippines I’d found among my father’s letters. The principal battles I marked in red: Balete Pass, Luzon, Leyte Gulf, Corregidor. The names of battles were actual physical places. My father had written about some young soldier from Texas named Melvin Smith who was killed in some place called Umingan. Where was Umingan? I located a speck on the map.

I pulled the crumbling rubber band off a clump of letters, opening the now-fragile, yellowing envelopes and V-mails. The creases in the thin paper were well worn.

My mother, until now the only reader of this correspondence, had bundled the letters by month; she’d numbered each letter in sequence—from one to four hundred and seventy-four. I arranged the months within the proper year, and separated the years into different boxes. I established a daily practice of logging the letters, then reading and transcribing them. By typing his words—passing them through my sight into my hands and onto my computer—I began to absorb them.

I noticed how his handwriting varied depending on the time of day (at mealtimes, in between skirmishes), his location (on a bunk, in a hammock, in a foxhole), the quality of illumination (flashlight, candlelight, electric bulb), his writing instrument (fountain pen or pencil), his level of exhaustion and discomfort. What would take longer to grasp was how his own experience fit within the chronology of the Pacific War campaign.

The letters could be divided into four main periods: stateside training (1943, at Camp Fannin in Tyler, Texas); more training overseas (1944, in New Zealand and New Caledonia); combat and its aftermath (most of 1945, in northern Luzon in the Philippines); and the United States Army occupation of Japan (October to December, 1945, on a navy ship and in garrison near Nagoya).

I’d set a goal for a given day, say, transcribe all the letters from December 1944, or half of the letters from January 1945. But once I’d begun, it was difficult to stop. My order would break down and I’d pull letters to read at random out of the boxes. What was February 12, 1944, like? What was happening the second half of June 1945? I’d start in the morning and then look up amazed to see the dusky northwest sky streaked with purple and red.

Knowing that his wife would read what he wrote both consoled my father and gave him the ability to observe what was happening around him more objectively. He also knew to temper his descriptions with reassurance. Her letters to him were a lifeline; in those gaps of time when he was unable to receive them, he suffered. They were constant reminders of a life worth living, a family to come home to, the ongoing daily saga of her life in Brooklyn—these were precious talismans. The constancy of their correspondence was unusual.

22 August 1944, South Pacific

I’m so glad you find my letters to you so satisfying. I have always written how much I enjoy your writing ability. I never realized that I have developed a style of writing of my own. I just write as though I were conversing with you. And these days when I am so on edge, thinking of what you are going through, it is an outlet for me—to keep writing to you. The lengthier the letter the better I feel. It helps take a little of the tension off me. In between pages I usually pace the floor, then come back and read your old letters and write some more. That process goes on all evening, until I am rescued by Wilbur who gets hungry and decides I have written enough and we ought to eat something.

Even in the stressful period of preparing and waiting to go into combat, he continued to write home.

24 November 1944, South Pacific

I can now see the point of view of the older fellows (older in terms of service). They write very seldom because, when the going gets tough and they don’t write at all, their folks at home aren’t accustomed to receiving a steady flow of mail, so they don’t mind it as much.

But I will continue writing whenever I get the opportunity because that is the way you would want it.

I’m thankful that I have you and Ruth as an inspiration and no matter how tough the going—I’ll get back to you both someday. Perhaps sooner than we dare hope we shall be back in each other’s arms and look back on this period of separation as a horrible nightmare.

There were periods of weeks, especially later during combat in Luzon, when the mail could not be taken out or brought in to the troops over the rugged mountain trails surrounded by the enemy. During those times, my mother had no way of knowing whether her husband had been wounded or was still alive. Her nerves were on edge, her imagination primed for disaster.

29 April 1945, Philippine Islands

Dearest,

I write tonight with a heavy heart. One of my close friends just went the way of Dr. Orange. He sure was a swell lad—tops in everything. He was one of our old timers. It was he that was expecting the visit from his wife who is an army nurse—and he was the one that I spent many hours tutoring in trigonometry. He had such a burning desire to complete his formal education. I’m so deeply shocked that he is gone. The Grim Reaper of War sure takes his toll and always he picks on the cream of our youth. God how much longer can it go on?

Though subject to army censors, his letters answered a question I had never dared to ask while he was still alive: “What was the war like, Dad?” I began to discover the texture of his experiences—his appetites, longings, fears.

Food was frequently on his mind. He dreamed of Dagwood sandwiches: corned beef, pastrami, rolled beef and salami with relish, cucumbers and pickles. He fantasized about “Italian food at Leone’s and Little Venice. Swedish food. Smorgasbord at the Stockholm. French food at Pierre’s. Chicken dinner at Mom’s and some good American cooking at home from the Settlement Cook Book—a way to a man’s heart.” My mother sent packages from Brooklyn containing sardines, shrimp, anchovies, olives, and pickled herring, which he shared with his buddies. He noted that her honey cake arrived spoiled. His fatigues were always dirty. His quarters were “miserably hot, comparable to a Turkish bath.” Living with so many other men was “similar to a cross-section of Coney Island and the bedlam of Times Square during the rush hours.” He longed for the comforts of home.

27 October 1944, South Pacific

Hello Dearest: I’ve been doing a heap of just plain thinking these days, but really it hasn’t been brooding. Mostly I think of little things such as sitting down at a table with real chinaware—and an easy chair with a hassock to put my feet on—and a pipe, pajamas, robe, and slippers—and a rug, a lamp and a beautiful symphony all blended together with you in every thought.

And being able to go to the refrigerator for an ice cold beer—and some fruit—and even chocolate milk—or honestly, just a quart of plain old milk.

Yesterday we were dreaming of a bathroom. How it would feel to step out of a steaming hot shower onto a bathmat—have real running water out of faucets and a real tiled commode and a large mirror to shave—and, I don’t have to go on—but it makes me feel better to write it down.

We spend time staring at ads in the magazines that arrive regular ma

il. I love most the ones that show a tumbler of whiskey and soda with ice cubes in it—and a man wearing a white shirt—and pictures of sport clothes like a plaid shirt. Gosh.

Will you make some ham and eggs when we get back? Real eggs—sunny side up—and not scrambled? Can I mess the Sunday Times all over the living room floor before you read it? Can I leave my sneakers all over the house and knock pipe tobacco on the rug?

The booming of the big guns woke him up from sound sleep. Some men did not take off their shoes for a whole month. They slept in all their clothes. They kept puppies and monkeys for pets. “You’ll find a monkey in almost every jeep or truck. The boys all like to play with them.” When the men bathed they often found themselves encircled by eyes; the native women liked to watch their lean bodies and muscular arms. A skinny white horse wandered through their camp one night, and it was a wonder it was still alive because “they throw grenades at shadows after all.”

With a letter written from New Caledonia, he enclosed two pictures of a young doe:

21 October 1944

The boys had caught it and were taking it for a mascot. Then some dumb bastard shot it and wounded it and left it to die.

Our boys found it the next day down the creek, and the medics brought it in on a litter and tried to save its life. They fed it condensed milk with an eyedropper but the doe finally died. The doctor diagnosed it as suffering from shock and loss of blood.

I thought you would like to see the pictures. I did the printing of them. How do you like the workmanship? Not bad for an amateur.

I guess I’m not descriptive enough to relate how the medics worked over the animal and how our whole company was interested in its welfare, always asking for last minute communiqués etc. I hope the two pictures get through.

Between Brooklyn and the Pacific Islands, my parents’ letters frequently crossed in the mail. Correspondence lagged, arriving fifteen days late in bunches of three or five. Once the mail was so backed up, my father received thirteen letters from Brooklyn in one day.

On my mother’s twentieth-sixth birthday, her father died of stomach cancer in New York’s Bellevue Hospital. That same night, she wrote a long letter to her husband, one of the few letters of hers to survive the war.

3 May 1945

Dearest Friend,

I am writing this letter so that I can bare my innermost thoughts, and relieve my pain and sorrow. I may never send this letter to you. Your sorrows are sufficient for you to bear right now, and I can’t burden you any more. But I need you desperately—and, well—at least writing helps some.

You see, Norman, today I said goodbye to my father.

I’ll never lose sight of the fact that you, too, have seen men die—men who are young, who had every right to live. Perhaps you, yourself, have had many a narrow escape. I know that my father was not a young man. I also know that no man is immortal. Only—Papa did not deserve to go as he did. I’ll skip the details, though you are most likely calloused to gruesome sights. The only fortunate phase in the whole tragedy was that Papa was spared being aware. He never knew what was happening. But we did.…

Oh! He was a stubborn man! He even died a stubborn death. He was a simple man—he asked and received very little in life. How he loved children. How he adored his grandchildren. Oh Norman! How he loved your Ruthie! And Papa loved you, Norman. Until the very last, he talked about how he prayed for your homecoming. He did so want to see you again.

I’ll always remember the relationship between my father and mother. Theirs was a love of years—a love of toil and constant struggle. I’ll always cherish the fact that when my father left for the hospital, Mama left out one item when she made a clean sweep of Papa’s belongings. She left his trousers hanging in the bathroom just as he had always done. I appreciate that fact for I recall that when I packed your belongings into the trunk, I felt badly. And what I left for last, and hated most, was taking the tie rack down and putting away your ties.

It was twenty-six years ago that I was born unto my parents. I made that day an occasion for my parents. And that date will be forever linked up now.

For on May 3rd, 1945, a date recording my birth—also records the date of my father’s death.

And so life goes—Anne

That sad letter crossed with my father’s V-mail, written that same day during combat in Luzon, apologizing for forgetting her birthday. Three weeks later, he still did not know his father-in-law had died.

21 May 1945

Today’s letter from my mother tells me your dad is feeling better. Please don’t keep anything from me. Let me know how your dad is getting along from time to time. It’s better that you tell me all your sufferings rather than keep them all to yourself. Break down to me once in a while; you’ll feel better that way.

Not until June 1945, a month later, did he finally write his tender letter of condolence, ending with, “We all have to take the passing of our parents at some time in our lives. It is the most bitter pill to swallow in one’s life. And so much harder for you because you didn’t have me with you to help share your burden. I hope this letter helps a little.”

MY FATHER’S LETTERS ranged widely in tone. In moments of boredom, lying in a hammock on a troop ship, he offered practical advice: what to say to tactless friends whose husbands weren’t away at war, but home making money. Or, words of comfort, reassurance that they would start over once the war ended: “Everything will be different when we move from New York to Los Angeles, the ideal place to raise our family.” During his first days of combat in Luzon, in January 1945, he described the appalling conditions that prevailed in a war zone: “My mother told me there would be nights like this! It rained so hard it broke down the stakes supporting our ponchos that were over our holes—our hole began to fill up and we were sleeping in mud. After a while the heat of our bodies made the mud tepid and it was a little more comfortable. The medics cooked some chicken in a helmet—and I had some of it for chow.”

After that, something mundane follows: “When you enclose stamps how about putting them in between wax paper—because they are always stuck to the envelope.” In February 1945, already combat-hardened, he requested, “Please don’t use the salutation ‘Hello Angel’ in your letters.”

The military censor always read over his shoulder. “I have an idea this letter is going to be a very long one. At this stage, the censor must be getting tired,” he wrote solicitously at one point.

The censor knew specific things about Private Steinman; he knew, for instance, that he had no respect for the chaplain. (“The Holy Mackerel” he called him, complaining that “the Chaplain is always telling me his problems.”) The censor knew intimate details: During rifle drill, Private Steinman had been daydreaming about his wife’s earlobes. The censor knew that Private Steinman’s dreams almost landed him in trouble with his tent mate:

I sleep in a pup tent with a very old regular Army man—my platoon sergeant. He is a swell guy who has been in the Army over ten years. He’s in his late thirties. While sleeping this afternoon, I was dreaming of you—and two people in a pup tent are very close to each other—and I had a great desire in my dream to kiss you. It’s a lucky thing I woke up just then because I’m sure the sergeant would have doubted me and wondered whether my intentions were honorable.

They both learned to read between the lines. There were code words to elude the censor’s eyes. Either my parents had agreed upon them in advance, which is unlikely since they didn’t know what combat would be like, or they counted on each other to decipher the meaning in context.

I puzzled over the enigmatic phrase “Hal Rubin’s gift” that surfaced so many times, as in “I’m nowhere near where I can get that gift for Hal Rubin.” It took me weeks to decode its meaning.

Hal Rubin must have been a friend or acquaintance back home in New York, the kind of pushy guy on the dance floor who’d cut in when you were happily partnering with your wife. Hal Rubin had apparently requested a war souvenir, the kind that could only

be procured where there were dead Japanese soldiers around. The name served as a code word for the front lines during combat, and sometimes even for the enemy himself. My father’s use of the enigmatic phrase shows how he both dreaded combat, and, conversely, yearned to get it over with.

16 November 1944

Hal Rubin still has several weeks before I can get him the gift that he asked for.

17 November 1944

I’m wondering a lot these days if I ought to get that little gift for Hal Rubin. After all, he never got any for us. If the opportunity presents itself I may—but I’ve decided not to go out of my way for it.

3 December 1944

I know I’ve been very incoherent in my letters of recent days but if you are confused please remember that I too am even more confused. And what annoys me most paradoxically is that I have to postpone and wait a little longer to get that damned gift for Hal Rubin. I am very impetuous and don’t like waiting, it always puts me on edge. I like to get things done and over with. But I suppose it is for the best.

Somehow I think that you’re not a bit angry about the delay and even wonder why I’m making so much of a fuss about the goddamned gift. But it is an outlet for me. I’ve been in a rut ever since I’ve joined this army—and I hate it very much. I want to do something and help get this damned war over with so that I can get back to you and everything dear.

12 December 1944

That gift for my pal Hal Rubin may come up pretty soon—and I’m kinda glad that it is. Although I never was really anxious or enthused about the whole thing. I like to get it over with so that I can give it to them, and then relax. I think we’ve been waiting long enough and I’m tired of waiting. So if you see Hal, don’t tell him or anyone about it, because I do want it to be a surprise.

The correspondence I was reading was, however, just a one-sided dialogue. My father had no choice but to destroy most of his wife’s letters to him as he moved from place to place. He kept them as long as he could, and read them over and over again.

The Souvenir

The Souvenir